Last Friday, the New York City Police Department announced that 25 people in Brooklyn had been hospitalized soon after smoking synthetic cannabis; by Monday, the count had risen to 56 people. Police also announced Monday that they had arrested 13 people in connection with distributing the drugs.

The cases don’t appear to be as gruesome as those seen in another ongoing outbreak, in which people suffered uncontrollable bleeding after taking synthetic weed likely tainted with rat poison. That outbreak has sickened more than 200 and killed at least four across several states. These incidents highlight just volatile these unregulated drugs can be.

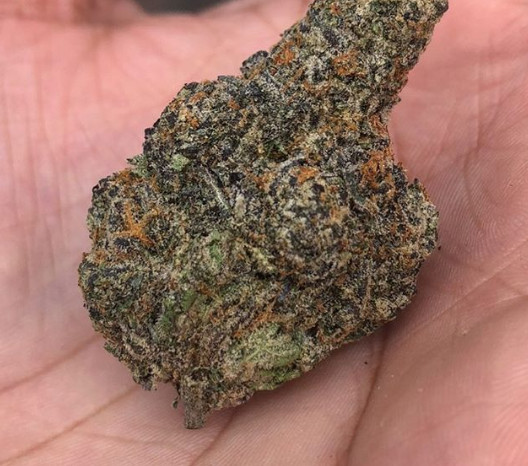

Synthetic weed is a bit of a misnomer, because these products aren’t trying to replicate the exact mix of chemicals found in cannabis, such as THC, the main ingredient responsible for the high. Rather, they’re designer molecules that are supposed to activate the same class of receptors in our brain cells that THC and other cannabinoids do, called the endocannabinoid system.

But synthetic cannabinoid chemicals, which are sprayed onto smokeable herbs or sold as a vaping fluid, are more much potent than those found in marijuana. And since the products are unregulated, the mix of chemicals could contain just about anything. That makes it easier for someone to experience symptoms like temporary psychosis, respiratory and cardiovascular problems, and even death. During the current NYC outbreak, the New York Times reported, emergency responders thought users were experiencing opioid overdose.

These dangerous side effects are made all the more likely by the murky legal territory surrounding the products.

The first synthetic cannabinoids were created by well-intentioned scientists back in the 1980s. They hoped to better understand how cannabinoids, mostly THC, affected the brain, according to Jenny Wiley, a behavioral pharmacologist at the nonprofit research institute RTI International who specializes in cannabinoids. Their work was initially relegated to the dustbins of academia, but things changed as the information age kicked into high gear around the 2000s.

“These patents and publications [on synthetic cannabinoids] laid dormant, but when the internet came along, someone, somewhere saw the opportunity to make money,” Wiley told Gizmodo. “THC was mostly illegal back then, but these other compounds were not, since they’re structurally different from THC. So that was really the start of so-called ‘legal cannabis.’”

These products, under brand names such as K2 and Spice, were freely sold in head shops and grocery stores for years before federal and state governments started banning specific cannabinoids following outbreaks of fake weed overdoses, including one that struck Brooklyn in 2016. But these bans have only set off an arms race, as manufacturers (likely based in China) have turned to using other synthetic cannabinoids to skirt these laws.

“Essentially they’re going through the whole list of synthesized compounds that were made in the past, and sometimes they get the chemistry right and sometimes they don’t,” Wiley said. “Sometimes these products even get sprayed with newly invented compounds, probably because they didn’t get the chemistry right.”

These newer synthetic cannabinoids can be even more powerful than older ones, raising the risk of dangerous effects.

“If you’re taking THC, that’s kind of like taking a little hammer and lightly tapping the receptors. But these newer ones are like a sledgehammer that’s being slammed really hard,” Wiley said.

The heightened potency of synthetic cannabinoids likely accounts for the severity of the New York cases. And though they don’t necessarily explain the earlier outbreak of bleeding (it’s still not known how or why rat poison was put in those drugs), both these episodes make clear the lack of quality control behind the manufacturing of synthetic cannabinoids, according to Wiley.

It’s unlikely that federal and state governments can ever reach the bottom of the well in banning every possible chemical that could theoretically be sold as fake weed, she noted. Likewise, despite the horror stories, demand for these products, which don’t show up on typical drug tests, seems to be steady, as does their supply. And there’s simply no telling how much of a gamble users are jumping into.

“When someone’s taking these drugs, they’re essentially a human guinea pig,” Wiley said, “because in many cases, these compounds have never been tested, even in animals.”

“You just don’t know what you’re taking,” Wiley added.

Credit: gizmodo.com