In the November 2016 election, 71% of Florida voters passed a medical marijuana law to allow patients with certain debilitating diseases like cancer, epilepsy, and post-traumatic stress disorder to access medical marijuana. Florida is now one of 29 states along with D.C. to legalize marijuana for medical purposes. While this is an important step to take towards broader drug reform, ultimately this new law will have very little impact on incarceration rates or racial inequalities of drug arrests. There are almost 100,000 people in Florida’s state prison system1, and about 45% of them are there for non-violent offenses, including 14.5% of them for drug offenses.2 People of color, especially African-American communities, have disproportionately been the victims of over-incarceration and the “war on drugs.”

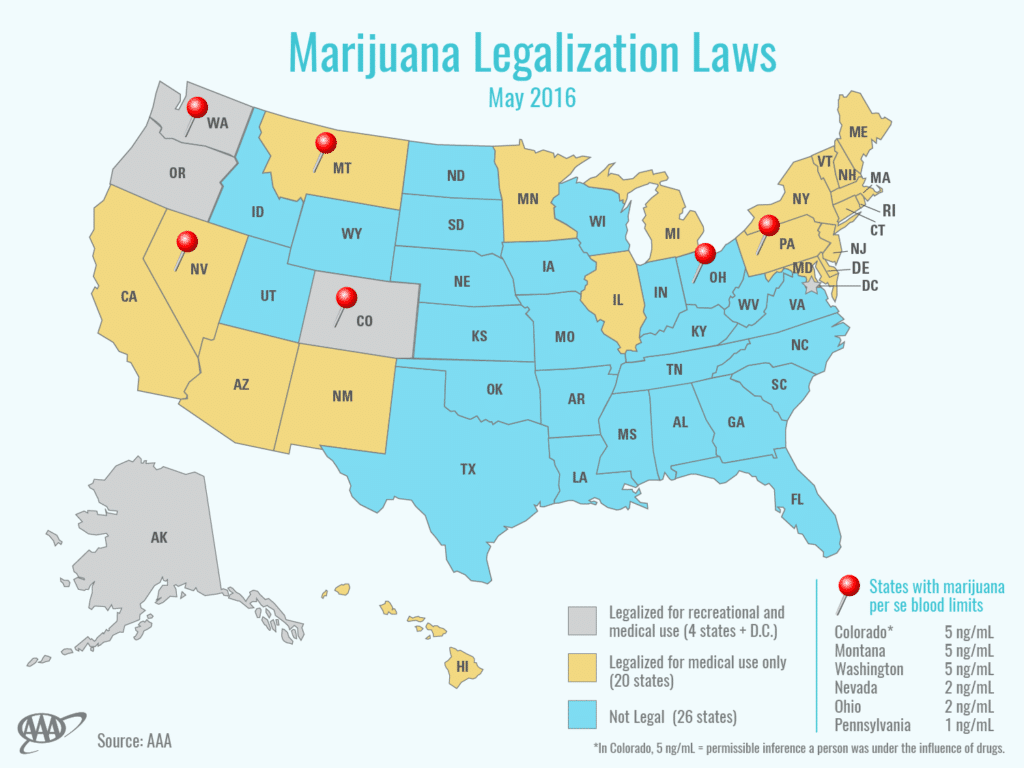

In 2013, the ACLU published a report entitled, “The War on Marijuana in Black and White,” which highlighted the racial disparities in marijuana arrests, prosecutions, convictions, and sentences. This report found that in 2010 there were 57,951 marijuana possession arrests in Florida and that even though the rate of marijuana use among whites and blacks is roughly equal, African Americans were 4.1 times more likely to be arrested for marijuana possession than whites.3 Although the progress of medical marijuana is important, it is not going to provide much or any help to the communities of color that continue to deal with over-policing and racial profiling. To really tackle the issues of over-incarceration and racial inequalities in marijuana arrests, decriminalization or legalization is necessary. In total, twenty-one states have enacted laws to stop arresting and jailing residents for possession of small amounts of marijuana.

Eight states have done this through legalization, essentially treating marijuana like alcohol. Thirteen states have decriminalized possession of modest amounts of marijuana. Decriminalization means it is still illegal to buy, sell, and grow marijuana, but individuals can no longer be arrested for possessing certain amounts. These laws result in people avoiding the life-altering collateral consequences of a criminal record and allow law enforcement to focus their time and resources on serious crimes.

The greatest beneficiaries of these laws arguably are communities of color that continue to deal with over-policing and racial profiling. Despite progress on a state level, unfortunately the opposite is happening on the federal level. U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced he would require federal prosecutors, with very limited exceptions, to seek the maximum sentence for all convicted drug offenders.

His stance is in direct contradiction to the gains made by the previous administration and civil rights groups like the ACLU that have been advancing the theory and practice of “Smart Justice.” “Smart Justice” initiatives, or “Smart on Crime” legislation, have resulted in more drug courts, increased drug abuse counseling services in lieu of incarceration, and saved many people from a downward spiral given the barriers that having a criminal conviction create for purposes of gaining employment, educational opportunities, and better and safer housing options.It is inconceivable that Mr. Sessions is unaware that harsh drug laws do not stop people from using drugs. If that were the case, illicit drug use would have been greatly reduced or eradicated decades ago. Instead, drug laws perpetuate the over-incarceration that has destroyed families and whole communities, and continue to disproportionately affect black and brown people. Unfortunately, at least one federal appellate court has ruled that, despite Congress’ prohibition on the Department of Justice from spending any money to interfere with state medical marijuana laws, that prohibition does not extend to probation conditions for those convicted of drug crimes. In U.S. v. Nixon, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit upheld a lower court’s sentence which included as a condition of probation that the defendant “refrain from unlawful use of a controlled substance and submit to periodic drug testing.”4 The defendant argued that the condition of probation violated Congress’ restriction on DOJ spending related to medical marijuana.5 The Ninth Circuit rejected this argument, reasoning that, pursuant to the Constitution’s Supremacy Clause, the CSA trumps Congress’ restriction and, therefore, prosecution and sentencing under the CSA remains permissible.

The significance of this decision and Mr. Session’s declaration is that, even though states continue to advance progressive drug law reforms, federal interference remains a serious threat to this movement. Therefore, proponents of decriminalization and legalization must continue lobbying their Congress members for at least a partial repeal or amendments to the CSA, and encourage their state legislators to use their political influence towards this end. While many believe reforming marijuana laws at the state level is inevitable, vigilance in the form of political advocacy remains paramount.

credit:aclufl.org