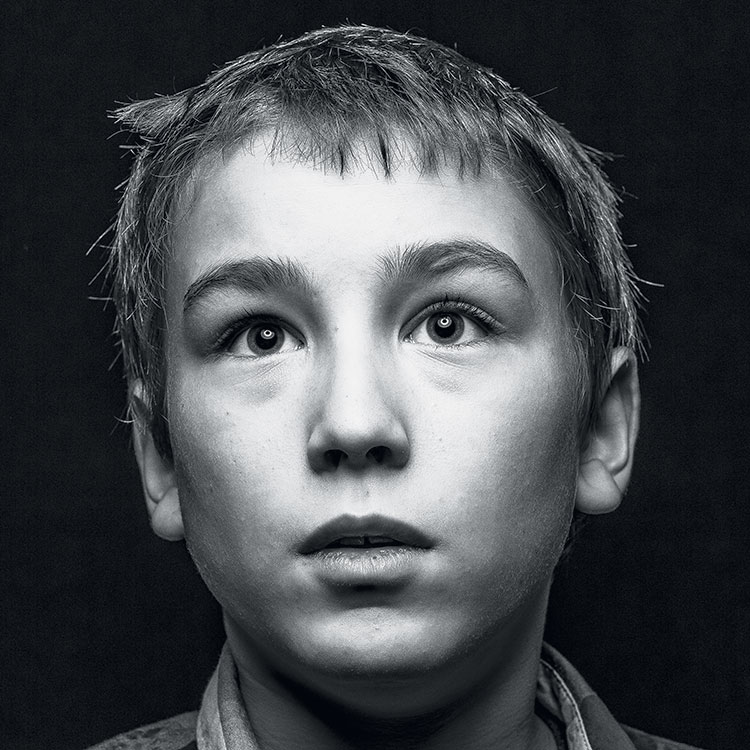

One night in 2016, Roman Salamon flitted from room to room in his Shaler Township home, doing what he usually does. Eleven-year-old Roman, who is severely autistic, was wandering around the house while the rest of the family watched TV, flapping his hands, tapping, clucking his tongue and making “eeeee” sounds. Not talking — Roman stopped speaking when he was a toddler.

Pennsylvania had just legalized the use of marijuana for serious medical conditions, including autism, and the state was giving parents “safe harbor letters” to buy cannabis medicines elsewhere until it was available here. Jennifer Salamon — Roman’s mother and the communications director of Autism Connection of Pennsylvania — had one of those letters.

She and her husband had read reports from parents saying cannabis oil helped their children with autism relax, wind down and focus. So that night she ordered a small bottle from a company in another state; when it arrived, she started putting drops in Roman’s juice.

The reaction, she says, was almost immediate. He was calm. He made eye contact. The flapping and tapping stopped. His teachers and therapists noticed a difference.

A few weeks passed. Then one night, as she was helping him get ready for bed, Roman said the first word he had said to her in a decade. It was “Mom.”

He had this look on his face like he was so proud of himself,” Salamon says.

But when the bottle ran out after a month, she couldn’t get a refill. The manufacturers no longer shipped out of state, fearful of federal prosecution. She got a replacement cannabis oil from Colorado; it helps Roman sleep better, but he hasn’t spoken again.

Now Salamon is excited to shop in a well-stocked Pennsylvania dispensary and consult with a licensed pharmacist about various products. She figures it will cost between $150 and $200 monthly — an expense not covered by health insurance. But it’s a small price to pay if Roman says “Mom” again.

This is the year Pennsylvania begins allowing the manufacture and sale of marijuana to patients with any of 17 qualifying medical conditions. The federal government still treats cannabis as an illegal drug with no currently accepted medical use, but 29 states (and the District of Columbia) now have programs like Pennsylvania’s — including every state on its borders.

Weed is no longer a red state/blue state issue. Republican-controlled legislatures passed medical marijuana laws in Harrisburg and Ohio in 2016 and West Virginia last year. A majority of voters in 2016 pulled the lever for both Donald Trump and medical marijuana in Florida, North Dakota and Arkansas.

Pennsylvania has the potential to become a lucrative market. One relatively conservative estimate, from the Washington, D.C.-based cannabis market analysis and consulting firm New Frontier Data, forecasts $88 million in legal marijuana sales in the commonwealth in 2018. In November 2017, the Pennsylvania Department of Health officially opened online registration for patient I.D. cards; more than 2,100 people applied in the first 48 hours.

Among Salamon’s options for local cannabis distributors: Cresco Yeltrah, a partnership between the Hartley family in Butler and an Illinois medical marijuana company. Cresco Yeltrah has dispensaries in the Strip District and Butler, with a forthcoming third location yet to be announced; it is also a producer, and its facility just off I-80 in Brookville, roughly two hours from Pittsburgh, was the first in the state to receive health department approval to start growing. Watched over by a network of video cameras, employees there tend to plants that are individually tagged and tracked on a state database from seed to sale. “It’s probably harder to get into my facility than to get into the Pentagon,” says Trent Hartley, chief operating officer, of the site’s security.

Maturing under grow lights, the plants there are nearly ready for their first harvest this month. Atop the familiar fronds of seven sawtoothed leaves, the flowering buds are powerfully aromatic and sticky with resin. But instead of drying those flowers to be smoked — which is still prohibited under state law — Cresco Yeltrah and the other growers will extract the resins and manufacture them into allowable forms: tinctures, oils, waxy concentrates, capsules, creams, pills, patches and pre-loaded vape cartridges.

Hartley is familiar with the parental anxiety Salamon is going through. His daughter Barrett began suffering from inflammatory bowel disease as a teenager about six years ago. Her condition was severe enough to require several emergency room visits, and one time, a full week in the hospital. She was miserable, and nothing the doctors tried seemed to work.

Desperately searching for a cure online, Hartley read research from Israel suggesting marijuana can ease gastrointestinal inflammation. He himself had started smoking pot as a teenager and says it unexpectedly cured his seasonal asthma. Maybe, he reasoned, it could help his daughter.

So Hartley bought what he considered a promising strain of marijuana from a California dispensary and smoked it with Barrett. “She never took a pill again, never saw a doctor again, never went back to the hospital again for constipation,” he says.

It worked so well that Hartley bought his children an expensive vaporizer so they also could use cannabis. Hartley’s son, now a college freshman, takes it for Crohn’s disease; his older daughter for fibromyalgia. And Hartley still uses it too; he says it alleviates chronic back pain from an old surgery and also helps him concentrate.

He then persuaded his father and brother to join him in a new business venture to supplement the family’s Butler County glass factories: marijuana farming. Teaming with Cresco Labs, a leading cannabis cultivator in Illinois, Cresco Yeltrah — the second word is Hartley spelled backwards — secured one of the 12 grower licenses the state awarded this past summer.

Cresco Labs founder and CEO Charlie Bachtell has similarly unexpected origins in the industry. He was the legal counsel for a Chicago-based mortgage company in 2013 when medical marijuana became legal in Illinois. Bachtell and a business partner had been looking for an entrepreneurial opportunity and decided this was ideal for their skillset. “It’s amazing how much being part of mortgage banking, the most scrutinized and regulated industry in America, prepared us to participate in the medical cannabis business, the new most scrutinized and regulated industry,” he says.

Success for Cresco Yeltrah and the other 11 growers and 26 dispensary operators the state has approved so far will depend not solely on how many patients want to buy medical cannabis. It also will rely on how many doctors are available to enable them to do so.

credit:pittsburghmagazine.com