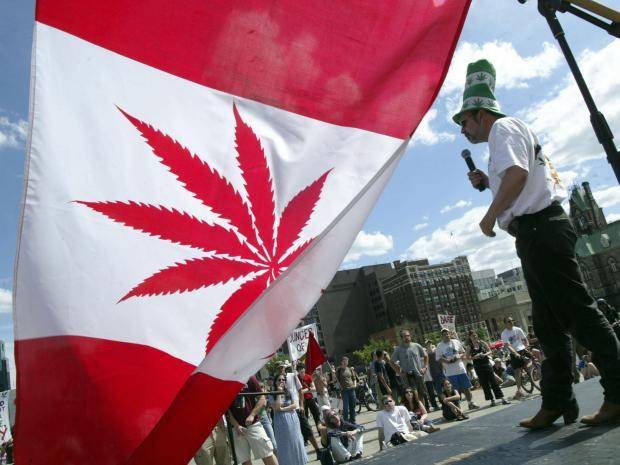

Canada’s Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has promised to legalize marijuana and his Liberal government recently introduced Bill C-45, the Cannabis Act, to Parliament.

The historic move places Canada at the forefront of global cannabis law reform, but critics across the country are speaking out about the potential dangers of the governments new plan.

I spoke with Kirk Tousaw – one of Canada’s most successful pot lawyers – about the good, bad and ugly of the new bill and how Canada’s cannabis community can continue to make their voices heard.

I think it’s important to recognize at the outset that the pathway to legalization is exactly that – a pathway and a journey – and we are taking a small step along that path, and in some senses an historic step.

This is the first time that legalization legislation has ever been tabled in the House of Commons and the first time cannabis policy reform has been tabled in the House of Commons in more than a decade. We’re only the second country in the world to be contemplating the legalization of cannabis at the federal level so those are all good things. Now, when you dive into the nitty-gritty of what’s been proposed, I have concerns – some deep concerns – about whether the end of the journey, at least in terms of the legislative process, is going to be what Canadians want and expect from our government.

There’s a 30 gram limit, not bad for a personal limit. But that is not of just any weed – that’s of marijuana you get from one of these Licensed Producers or theoretically grown yourself?

Yes, here is where we run into the devil in the details. The government has proposed that people be able to possess, in public, a maximum of 30 g of cannabis – and that’s dry cannabis. There’s an equivalency ratio to talk about – either fresh cannabis or concentrates and things like that – but let’s stick with the 30 g in public. That’s an arbitrary number obviously, they could’ve said 31, they could’ve said 40, they could’ve said 80, they could have just said you can possess cannabis in public as long as not for the purposes of trafficking. But they pick 30 g and that’s consistent with most jurisdictions. So, while I think it’s sort of silly to have any limit (I can drive up to the local liquor store and back the truck up and fill it up with enough vodka to kill small town and would have no problem at all), we knew there was going to be a limit and 30 g is as reasonable as any other limit (which is to say arbitrary an unreasonable) but it’s a start.

The difficulty is they said that has to be 30 g of something that’s not “elicit” cannabis. Elicit cannabis is essentially defined as cannabis you’ve obtained from a source other than a legal source. That presumably means if you go into your local store and buy cannabis that’s been produced by a lawful producer and sold lawfully, you are perfectly OK. But if you have some other cannabis in your possession, you can’t have any, or you’re breaking the possession laws.

How police are going to be able to enforce that kind of ridiculous differentiation is beyond me. I don’t think we’re going to be equipping our local patrol officers with devices that enable them to test the genetic heritage of the cannabis they find on people. And even if we did, since you can grow it lawfully, and that means you can breed it lawfully to a certain extent, those tests wouldn’t even yield conclusive or relevant evidence. So I think we have a kind of distinction here that can’t be enforced in the law. And when you have a law that sets up that problem from the front end, it seems to me that rational people would say, why would you even bother trying that distinction if it’s completely unenforceable?

It seems like there are a few things in this set of rules that are head-scratchers.

I think that’s a fair description.

Another one is super-heavy penalties for selling to minors: if an 18-year-old sold to a 17-year-old, they could be looking at 14 years in jail.

Yes, the maximum. That’s really out of whack with how we treat the sale of other substances. For example, if you operate a store – and this is a store licensed by the government given the privilege to operate a commercial enterprise – and you sell tobacco to a minor, you’re probably going to pay a small fine. If you sell booze to a minor, you’re going to pay a fine. No one’s going to jail for doing that. Yet, like you say, the 18 or 19-year-old that’s maybe even still in high school with his 17-year-old buddy that sells or even hands that person for free a little bit of cannabis, they could be facing a maximum of 14 years in prison. It makes no real sense, and is completely out of whack with the reality of what’s going on in Canada currently today. I think at the end of the day that the penalty is going to be very hard to support or enforce in the judicial system. I just don’t think judges are going to have any of it.

Part of the good news is that all of these penalty provisions that are proposed in the cannabis act are all hybrid offences. In other words, they can be preceded by way of either summary convictions or indictments, and in the law that draws a pretty dramatic difference. So if you’re in the summary conviction area, the maximums are much less significant. $15,000 fine and 18 months in prison are the maximums, if the Crown proceeds by way of summary conviction. There is some flexibility built into the regime and hopefully we don’t have these really out of whack scenarios where people are being punished incredibly harshly for activities that don’t deserve that kind of a sanction, particularly in comparison with deadly drugs like booze and tobacco.

Some other stuff that seemed troubling to me was related to driving limits – nanogram limits and the idea of saliva testing.

It’s another one where you have to just sit back and say this stuff is not really enforceable. Certainly not enforceable in any kind of fair manner. Number one, the idea that the Charter is going to allow police to engage in random, suspicion-less drug testing I think is unlikely. I just think that it’s not going to survive constitutional challenge. Even if you did, the next question is what evidence is yielded. At the end of the day, in my opinion, the evidence of how many nanograms per millilitre of THC metabolite you have in your blood is not particularly relevant to the issue of whether or not your ability to drive was impaired. So what you have is a test that’s producing evidence that is irrelevant to the real issue and the real crime of driving while impaired.

When you have something that encroaches on people’s freedom and privacy in a significant way, that yields no relevant evidence to the underlying question, “was that person impaired while driving?”, it just looks like a real mess that can’t survive the first set of challenges.

And oh by the way, the nanogram per millilitre limit is so shockingly low that you could have consumed cannabis a week ago – or two weeks ago – and still test over the 2 nanogram per millilitre limit. That again speaks to the irrelevance of the evidence that’s been gathered by these highly intrusive methods.

I think it’s important to draw the distinction between the production side of things and the retail side of things. It’s very clear the federal government is going to retain jurisdiction over production and manufacture of cannabis and cannabis products. Those rules have not been set down in the bill. They are going to be left to a rulemaking process that will occur down the line. So we don’t have any real guidance and clarity from the government as to what the commercial end of the industry is going to look like from a production standpoint.

It is very clear the provinces are going to be allowed to regulate retail. A part of what is going to be mandatory is that any stores licensed by the province to sell cannabis to adults are going to have to obtain that supply from sources that are licensed to grow it by the federal government. So again, we don’t have any real clarity about that process. If we run into a situation where to be a legal dispensary you have to buy your supply from this very artificially limited group of Licensed Producers we have now – or maybe a few more – it’s just setting itself up for failure in my opinion, and for an inability to compete with, not just the existing network of dispensaries that are out there, but the existing network of people that just sort of sell cannabis out there.

We have to remember that virtually all of the cannabis produced and sold in this country right now is done so unlawfully. If the government wants to eliminate that portion of the industry, this is not the way to go about doing it. What you need to do is bring those people out of the shadows and into the light and create a system of rules that are fair and that are commensurate with the potential harms and benefits of consuming cannabis and growing it. You need to make it easy for Canadians to participate in the legal system as opposed to going and sort of doing what they’ve been doing for the last hundred years, which is just breaking the law in order to access cannabis. So there’s a lot yet to be determined and I think each province is going to look a little different on the retail end.

Certainly one thing I think we need to be advocating very hard for over the next year or so as this moves through the legislative process, is some kind of carve-out that allows provinces to have a regulatory role in licensing small craft producers that want to supply local marketplace or to have on-site sales, much in the way that breweries have special licensing if they are simply going to be supplying their local communities from the place manufactured. Seems to me that this kind of role ought to be regulated by the provinces and not so much by the federal government.

If you want to license the big players in the industry – they’re going to be there as they are in every industry – that makes some sense, but there’s no reason that if somebody on Vancouver Island, B.C. wants to open a vineyard-model cannabis farm with a little reception area and tasting room and some offsite sales, there’s no reason that should be regulated at the federal government level. That should be within the jurisdiction of the provinces.

What about extracts and edibles? Were they mentioned in the bill?

Pretty silent on that point. It really looks like, at least at the starting block, there’s not going to be a provision for pre-manufactured edibles. There’s going to be some provisions for the sale of cannabis oil and people are going to be able to make their own edibles and extracts. It does seem like there is some thinking going into concentrates. One of the things that this has done is set up an equivalency factor where a quarter gram of concentrate equals 1 g of dried cannabis for purposes of the 30 g possession limit.

There is some thinking going into that, as there is also with with the ACMPR, a restriction on the use of organic solvents to make derivative products – basically things that can blow up. Again I think the problem here is that government’s 10 years in the past in the extract industry. When open blasting with butane was the way people were making butane-based concentrates, for example, well sure there were some safety risks there that you need to address. But if you’re running a high-quality lab-condition closed-loop system, nothings going to blowup. So those kind of automatic restrictions on the use of particular things like butane don’t make a lot of sense in todays industry.

Right now Marc and Jodie Emery are facing life in prison, at a time when the government is going to allow other people to do exactly the same thing and sell marijuana. Is that constitutional?

Well, I think it’s up to a judge to determine that. There are principles, Section 7: jurisprudence of arbitrariness, gross disproportionality and overbreadth that certainly come into play. I would anticipate making an argument that it is grossly disproportionate to impose consequences – up to and including life in prison – on people that sell cannabis, when other people that are engaged in exactly the same behavior are getting a license to do it. Those battles have yet to be fought. I expect they will be fought.

It’s a journey, right? I’ve appeared on panels with lawyers representing the craft beer and craft wine industry and, 100 years post-prohibition, there are still a lot of bizarre and stupid rules in place affecting peoples’ ability to get into the alcohol business or to transport good wine across provincial lines. There’s a lot of dumb and stupid and arbitrary and in some instances harmful rules out there in a lot of industries that need to be fixed. So let’s get to work on fixing them. It starts today with advocacy to try to get some amendments to this legislation that will stand off some of the roughest edges. Then when it gets passed, it’s up to the courts to pronounce on whether or not meets the dictates of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

This is a step on the path. There is a legislative process we need to go through. It includes hearings before both the Justice Committee in the House of Commons, as well as potentially committees in the Senate. There’s a lot of opportunities for advocacy. People need to make their voices known to their local members of Parliament, their local members of provincial legislative assemblies or provincial houses and territorial governments. At the end of the day, politicians are supposed to be guided by the will of the people. We need to be telling them what our will is, so they can understand it.