If you ever purchase cannabis from a dispensary in Oregon—where pot has been legalized for adult use since 2016—you’ll receive an advisory message you probably won’t read. You’re just here for the weed, right? But say your curiosity commands otherwise. What you’ll read isn’t like the Surgeon General’s warning accompanying cigarette packs. The message’s author, the Oregon Liquor Control Commission (OLCC), which regulates the distribution and sale of cannabis in the state, isn’t concerned with your health exactly. No, instead the OLCC warns parents and adults that consuming marijuana in front of children will make them look… too cool.

“Children want to be like their parents and other adults in their lives,” reads the OLCC’s officious, red-block lettering. “When you use marijuana in front of them, they may want to use it, too. You can keep them safe and healthy by not using marijuana when kids are around.”

No one’s positing that kids should use marijuana recreationally—but oh my, have times changed. Cannabis was once so dangerously cool, the youth’s drug of choice, embedded in the Summer of Love, the counterculture movement and college dorm rooms across America. This idea of marijuana as civil disobedience is dying, thanks to legalization. So what does cannabis as a culture, a lifestyle, a way of being, represent now? Do kids even consider it cool anymore? Does anyone?

Data from Monitoring the Future, an organization that has surveyed national drug usage rates of high schoolers every year since 1975, demonstrates how cannabis legalization has impacted teen consumption patterns. Since 2005, the number of 12th graders across the country reporting they’ve used cannabis in their lifetime has hovered below 45 percent. Legalization efforts over the past 15 years—during which 33 states have legalized medical marijuana and 10 states have legalized recreational use—have not changed that figure. Meanwhile, in 1980, 60.3 percent of 12th graders admitted to trying marijuana in their lifetime, the second-highest figure ever recorded.

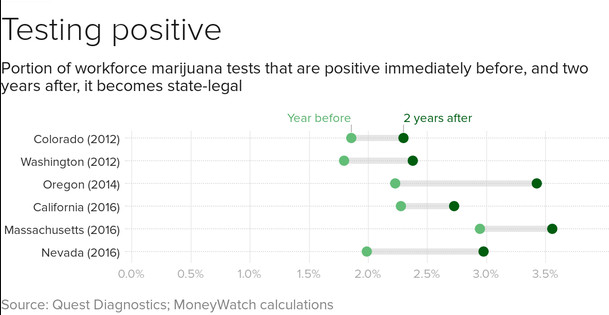

If anything, the data indicates legalization discourages teens from using cannabis. Only nine percent of Colorado teens aged 12 to 17 used marijuana monthly in 2015-2016, a statistically significant drop of two percentage points from the year prior, according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Washington, Alaska and Washington, D.C. also saw similar declines in teens reporting cannabis usage in the past month. In a flip of stereotypes, middle-aged parents are more likely to use marijuana than their teens, says the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Seriously, teenagers just don’t do drugs like they used to. Outside of cannabis, last year represented the lowest-ever figure of lifetime drug usage from Monitoring the Future’s 40-year-plus dataset. So don’t worry parents—data suggests your kids don’t consider you, or your drugs, particularly cool at all.

“There’s an aspect of when pot was illegal, it was a forbidden fruit, rite-of-passage sort of thing,” Russ Belville, a longtime cannabis reform activist and owner of a Portland 420-friendly bed and breakfast, told Observer. “Now that pot is legal, it’s mom’s Chardonnay, it’s dad’s cigar. It’s not cool anymore. It’s kind of lame to the kids.”

That’s the case for Whittaker Bangs, a 14-year-old Denver teen attending Littleton High School. Both of his parents smoke marijuana, while his mom works as creative director at Grove Spaces, a startup opening high-end cannabis consumption spaces in Denver. He doesn’t use personally, and isn’t sure if he will when he reaches legal age.

“I don’t believe it is a boring activity, but I don’t think it’s something that I would be willing to drop everything to do,” he wrote over email.

That sense of mild anarchy is also disappearing from stoner culture, which is often mistaken for cannabis culture writ large. Consider Cheech and Chong, Willie Nelson, Snoop Dogg. Historically cool guys, sure, but these are cannabis brand names now, each with their own line of weed products—no longer sticking it to the man, just doing business, man. These OGs of cannabis no longer qualify as producers of vibrant, vital culture in the cannabis space. Yet when most imagine someone associated with weed, it still isn’t mom and dad; it’s more likely Red Headed Strangers and Snoop to the Double G, baby.

When examining cannabis as a culture in 2018, you realize a gulf of misinformation exists between the mainstream consumer and the cannabis community. Who uses cannabis and what for are questions that don’t have easy answers anymore. Maybe they never did. But that myth of pot leaf stickers, Rastafarian flags and junk food binges was so pervasive, it fooled many into thinking they knew what a cannabis consumer was—a lazy stoner, a rebellious teen, an idyllic hippie. Now, thanks to successful activist efforts over the past 20 years, the identity of cannabis users has never been more difficult to categorize.

“Prior to legalization, everyone kind of had their [own] idea about what weed is, who it’s for, and why one might use it,” said Anja Charbonneau, editor-in-chief of Broccoli, a rigorously designed and edited cannabis magazine by and for women. “But now, we have all these different narratives to follow and to try to keep up with and new ways to try to identify with it.”

Yes, add the rapidly shifting culture of cannabis to the list of news items you can’t keep up with. We probably won’t understand how radical this time period is—somewhere between dismantling prohibition and real scientific understanding of cannabis—until years later. What happens when lawlessness, previously a defining characteristic driving who became a stoner, transforms into legislation? As Belville told me, “Prohibition created alliances and cliques and groups out of necessity that legality is beginning to erode.”

The exclusive cool kids club of cannabis is over. Moms use it, Elon Musk uses it, Canada says most of its police can use it (off-duty, of course). The number of Baby Boomers who have used it has doubled since 2006. Those aged 65-plus have seen a significant uptick in monthly marijuana users as well (that figure was virtually zero in the mid-2000s). Every demographic you previously wouldn’t have dared suspect of using cannabis is now experimenting with the plant. Perhaps, the OLCC should actually be warning teens about their grandparents lighting up.

Like all niche cultures assumed by the mainstream, marijuana has been shedding old skins and gaining new ones along the way. Ian Van Veen Shaughnessy, CEO of Rare Industries, told Observer that the cannabis world now “contains a lot of numerous and nuanced voices.” Under the Rare Industries umbrella, he runsQuill, a vaporizer pen that prioritizes micro-dosing and provides a considered, minimalist design. Quill’s brand, as well as Charbonneau’s Broccoli magazine, represents a new aesthetic coursing through cannabis—seriously considered, but playfully concocted.

Shaughnessy believes cannabis sits on the precipice of cultural reinvention, like coffee did in the ‘90s and craft spirits in the mid-’00s. He’d know, too. He owned a café, sold it, had a brief career as a competitive barista, then co-founded a micro-distillery in Chicago, before running Rare Industries.

“Coffee’s a great analogy for this because you’ve got all these great micro roasters, you’ve got a number of surprisingly great, pretty large companies producing some really good coffee as well. It’s not just one thing or the other, but it can contain all these multitudes, and cannabis is following the same path,” Shaughnessy said.

To be fair, cannabis was long overdue for a rebrand. If you’ve noticed, I have mostlyreferred to it as “cannabis” throughout this article. This was intentional, as it’s what serious operators within the space call it. Some outsiders poke fun at this, but also, it’s literally the name of the plant. Whenever I hear someone say “pot,” I assume they’re over the age of 40 and probably used to be a hippie. “Weed” is serviceable, but also describes an unwanted presence in any self-respecting garden. No word carries more historical baggage than “marijuana,” a term with unknown Mexican origins. Harry Anslinger, the infamous anti-cannabis crusading bureaucrat, used the exotic-sounding word to stoke the xenophobic fears of white Americans to instigate prohibition in the 1930s.

Hopefully none of that sounds familiar to you today.

Thanks to prohibition and persistent federal persecution, our understanding of cannabis, including its functions, its molecular complexities and its mutability, is rather opaque.

Credit: observer.com

“The most important rebrand is really just the stripping away, like, I don’t think we need to give cannabis a new identity,” explained cannabis journalist Lauren Yoshiko. “We need to get to know its original identity before the anti-drug laws started happening and the Mexican-American battles began because that, to me, is the best way, the healthiest way to help cut through the misinformation.”

“I think possibly using ‘cannabis’ as a word is another part of that puzzle of helping people understand that it’s just a plant,” she added. “I’m not trying to teach you about a new complex drug that you should be less scared of. I’m trying to remind you, it’s just a plant.”

Yoshiko isn’t alone in this writerly pursuit. This year saw literary authors like Michael Pollan and Tao Lin openly embracing cannabis and psychedelics, publishing How to Change Your Mind and Trip, respectively. Though Pollan was an early pioneer in elevating cannabis’ abilities as a plant, it’s Lin who situates himself inside the growing camp that considers cannabis a dietary essential. Shaughnessy and Magical Butter CEO Garyn Angel expressed similar sentiments to me, with Shaughnessy arguing that many newcomers reject this notion because they misuse cannabis their first try. Puffing a joint when you’ve never imbibed cannabis is like chugging three shots of Bacardi 151 for your first drink, Shaughnessy said.

In Trip, Lin successfully positions cannabis in its “millennia-long relationship with humans,” frequently citing psychedelic trailblazers like Terence McKenna and Kathleen Harrison. While marijuana’s proficiency as an anti-inflammatory is nothing new, Lin explains why that’s important for everyone, especially for those not in immediate physical pain.

A 2015 paper in Emotion referenced in his book “showed that clinical depression is associated with high inflammation,” Lin wrote over email. The “strongest relationship,” researchers noted, between inflammation levels and measuring positive emotions was found in awe, “followed, not closely, by joy, pride, and contentment,” Lin writes in Trip.

Aesthetic-driven, plant-forward, health supplement. Cannabis may have lost its edge, but maybe that wasn’t as essential to its nature as we thought. When the lingering stigma of reefer madness dissipates, foundations of language and understanding can develop around cannabis. Much like popping open a beer after work doesn’t totally define a person’s lifestyle or value system, neither does using cannabis. We’re seeing “this entire mainstream shift in cannabis away from being something that stoners and hippies use to something that literally everybody uses,” Shaughnessy explained.

Everybody includes Republicans, rappers, veterans, socialists, seniors, weekend warriors, soccer moms, college grads and so many more. Cannabis clearly doesn’t have the burden of being “cool” anymore.

Credit: observer.com