Oregon state lawmakers who fear heightened marijuana enforcement by federal agents overwhelmingly approved Monday a proposal to protect pot users from having their identities or cannabis-buying habits from being divulged by the shops that make buying pre-rolled joints and “magic” brownies as easy as grabbing a bottle of whiskey from the liquor store.

The bipartisan proposal would protect pot consumers by abolishing a common business practice in this Pacific Northwest state where marijuana shops often keep a digital paper trail of their recreational pot customers’ names, birthdates, addresses and other personal information. The data is gleaned from their driver’s licenses, passports or whatever other form of ID they present at the door to prove they’re at least 21 as required by law.

The data is often collected without customers’ consent or knowledge. It is stored away as proprietary information the businesses use mostly for marketing and customer service purposes, such as linking their driver’s license number with every pot product they buy so dispensary employees are better able to help out during their next visit.

The measure that passed 53-5 now heads to Democratic Gov. Kate Brown, who is expected to sign it into law.

It would bring Oregon statutes in line with similar laws already in place in Alaska and Colorado and self-imposed industry standards in Washington state — the only other three U.S. states were where recreational cannabis is actively sold in shops to consumers of legal age.

“Given the immediate privacy issues … this is a good bill protecting the privacy of Oregonians choosing to purchase marijuana,” state Rep. Carl Wilson, a Republican who helped sponsor the bill, said before the final vote.

Upon the bill’s signing into law, Oregon pot retailers would have 30 days to destroy their customers’ data from their databases and would be banned from such record-keeping in the future. Recreational pot buyers could still choose, however, to sign up for dispensary email lists to get promotional coupons or birthday discounts. The bill’s provisions do not apply to medical marijuana patients.

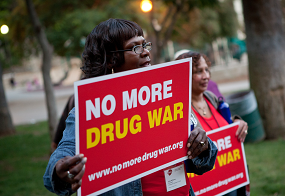

Oregon’s move was one of the first major responses to mixed signals about President Donald Trump administration’s stance on the federal prohibition on marijuana, which is legal for recreational use in eight states plus Washington, D.C., and legal for medical purposes in more than half the country.

Worries began in late February when White House spokesman Sean Spicer first signalled a crackdown may loom on recreational cannabis. A few weeks later, U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions said medical cannabis has been “hyped, maybe too much” and is “only slightly less awful” than heroin. Trump, however, has previously suggested the marijuana issue should be up to the states.

Last Monday, the governors of Alaska, Colorado, Oregon and Washington state asked for clarity about the Trump administration’s policy in a letter addressed to Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin and U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions, whose agencies took a low-priority approach to marijuana enforcement under President Barack Obama’s direction. Two days later, in a memo to more than 90 U.S. attorneys, Sessions said DOJ will look at marijuana as part of a broader crime-reduction policy review through mid-summer.

Congress, meanwhile, is gearing up for April 28, when funding for the federal government is set to expire along with its so-called Rohrabacher-Farr amendment, which has blocked federal funds from being used to interfere with states’ medical cannabis laws since 2014.

U.S. Rep. Earl Blumenauer, D-Oregon, says he and Rep. Dana Rohrabacher, D-California, plan to push for the amendment’s renewal ahead of its expiration in two weeks.

“It’s pretty clear the (marijuana) prohibition has not worked,” Blumenauer told the Associated Press. “These questions are to be expected and they need to be dealt with, but it’s hard to envision going back.”

credit:420intel.com