When Californians voted to legalize marijuana last year, they also voted to let people petition courts to reduce or hide convictions for past marijuana crimes. State residents can now petition courts to change some felonies to misdemeanors, change some misdemeanors to infractions, and wipe away convictions for possessing or growing small amounts of the drug.

“We call it reparative justice: repairing the harms caused by the war on drugs,” says Eunisses Hernandez of the Drug Policy Alliance, a nonprofit advocacy group that helped write the California ballot initiative.

Colorado, Maryland, New Hampshire and Oregon also have made it easier for people convicted of some crimes of marijuana possession, cultivation or manufacture to get their records sealed or expunged, which generally means removing convictions from public databases. Massachusetts lawmakers are considering a criminal justice bill that would, among other changes, allow people to expunge any conviction that’s no longer a crime, such as marijuana possession.

These efforts by states that have legalized or decriminalized marijuana are part of a national trend toward making it easier for people to seal or expunge a range of convictions. Americans with a criminal record — whether it’s marked with felonies, misdemeanors or both — can find it harder to get a job and find housing.

Hernandez and other social justice advocates say marijuana legalization should be paired with criminal justice reforms that help people convicted of past drug crimes rebuild their lives.

Yet allowing people to seal their criminal records or reclassify convictions is not the rule in states that have legalized or decriminalized possession of small amounts of marijuana. Bills that would remove or reduce convictions on people’s records are often opposed by lawmakers and prosecutors who argue that people who knowingly violated prior laws shouldn’t be let off the hook just because the law changed.

California has done more than any other state to require judges to excuse residents’ past marijuana crimes. That’s because the state took the issue to voters, Hernandez said. “Through the Legislature, we would not have gotten this.”

The Expungement Debate

In states that have legalized marijuana, some lawmakers say reducing old marijuana-related convictions is a no-brainer. “Since this is now the law of Nevada, it’s important that we allow folks who have made these mistakes in the past to have their records sealed up,” said Nevada Assemblyman William McCurdy, a Democrat who proposed a bill on the issue this year.

McCurdy hails from a poor area of Las Vegas. He knows people who have been convicted of possessing an ounce or less of marijuana — formerly a misdemeanor — and who are struggling to overcome the black mark on their record, he said. “They’re labeled now.”

After Oregonians voted to legalize marijuana possession, in 2014, most lawmakers agreed it was only fair to give people relief for past crimes that had become legal in the state, such as possessing up to an ounce of marijuana or growing up to six marijuana plants.

Provisions that allow certain records to be sealed were an uncontroversial part of a 2015 law that codified the ballot initiative, said Amy Margolis, a lawyer and director of the Oregon Cannabis Association, a trade association and advocacy group. It helped that Oregon already made it fairly easy for people convicted of minor crimes to get them set aside, she said.

Colorado lawmakers took more convincing. The Legislature considered a bill in 2014 that would have allowed people to petition to seal records of marijuana possession convictions that the state no longer considered illegal. But the bill died in committee after facing opposition from prosecutors.

“[The bill] creates a horrible precedent by retrofitting criminal sanctions for past conduct every time a new law is changed or passed,” Carolyn Tyler, a spokeswoman for Republican Attorney General John Suthers, told The Denver Post at the time.

District attorneys opposed the bill because it would have allowed small-time drug dealers to get their records sealed, said Thomas Raynes, executive director of the Colorado District Attorneys’ Council. “There were many cases of distribution that were pleaded to low-level [possession] felonies,” he said. This year, Colorado enacted a less controversial law targeted only at misdemeanor possession.

Proposals in other states also have been stalled by concerns that they’d force judges to let lawbreakers off the hook. In Washington, an oft-proposed bill that would require judges to vacate convictions for possession of fewer than 40 grams of marijuana has gone nowhere, partly because possession of 28 grams to 40 grams is still a misdemeanor in the state.

And in Nevada this year, the governor’s veto pen stopped McCurdy’s bill that would have required judges to seal records and vacate judgments for marijuana offenses that are now legal.

Limited Impact?

Defense lawyers and other advocates for decreasing penalties for nonviolent drug crimes say that sealing someone’s record can change their life. Yet state data from Oregon and California — the states that have done the most to allow people to take convictions off their records — suggest that so far, only a fraction of people with marijuana convictions have asked to get them sealed or set aside.

Nearly half a million people were arrested for marijuana crimes in California over the past decade, according to the Drug Policy Alliance. But California courts have received just 1,506 applications for reclassifying past marijuana-related crimes since state residents gained the option to do so last year.

The Drug Policy Alliance also says that more than 78,000 convictions could be set aside in Oregon. But courts received just 388 requests for set-asides in cases that involved a marijuana charge in 2015, 453 in 2016, and 365 so far this year, according to the Oregon Judicial Department.

It could be that many people just don’t know they can get their records sealed. Marijuana industry and legal defense groups have hosted free events in both states to help people file the right paperwork — though in both states, lawyers say filing a petition is straightforward enough to handle without an attorney.

Another problem may be that many people have complicated criminal records, Margolis said. “Those people — they have not benefited.”

Courts are more likely to reject petitions from people with long criminal histories, Margolis said. For instance, someone’s conviction for marijuana cultivation might be paired with a money-laundering conviction, a delivery conviction, or a criminal-mischief conviction because a house was vandalized.

Some people may just decide that hiding their conviction from view isn’t worth the hassle. If someone has another crime on his record that can’t be wiped away, say an unrelated felony, he might not bother to eliminate a minor marijuana conviction.

One of the convictions that can be sealed in Colorado and California is possession of an ounce or less of marijuana. But in both states, even before marijuana possession was legalized, possession of a small amount of marijuana was just an infraction or a petty offense, punishable by a $100 fine.

Still, the California ballot initiative’s emphasis on criminal justice reform and releasing people from the burden of past crimes may be the new normal moving forward. The initiative has become “the gold standard,” said Art Way, director of the Drug Policy Alliance’s Colorado office.

He said that activists in New Mexico, New Jersey and New York are all lobbying for racial justice and, to some extent, retroactive relief for marijuana crimes.

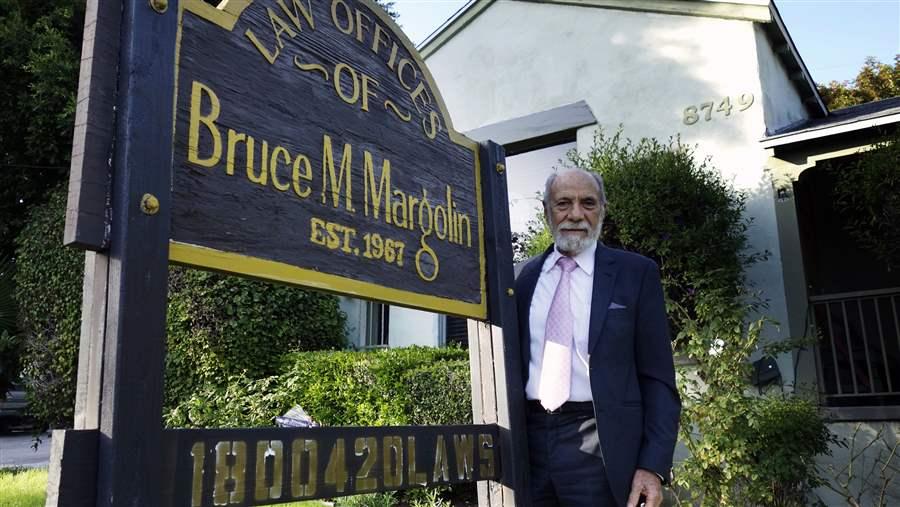

credit:420intel.com