Melody Cashion rattles off the list of drugs she once needed just to function.

Lyrica, Gabapentin, methadone, oxycodone, valium.

There were more. But those were the every day ones.

The drugs stemmed the pain from a genetic nerve disorder, a disease the 44-year-old, Marshall County woman has struggled with since childhood. They allowed her to have something resembling a normal life, but she was often in a zombie-like state — and that was better than the alternative.

“If I missed a dose, I would get sick,” she recalls. “If I tried to stop, I would get sick. I ended up in the hospital several times.”

The withdrawal symptoms were causing her to vomit and get dehydrated.

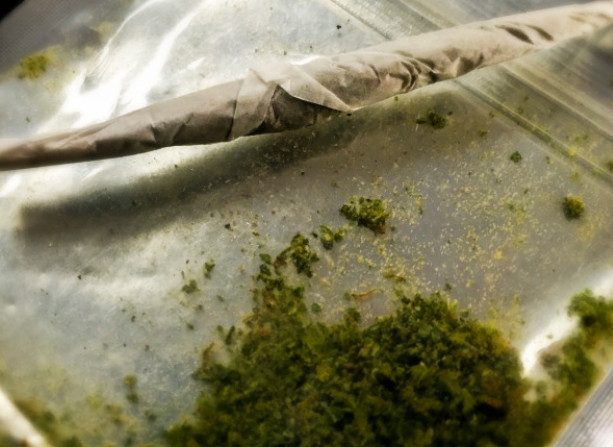

Cashion says that all ended when she began to smoke marijuana regularly a couple of years ago. One toke every two hours.

One promise made by supporters of medical cannabis is that it’ll help curb the state’s epidemic of pain pills. The idea is that marijuana could be a less addictive substitute for opioids.

There is some research to back this theory up, but not nearly enough for skeptics. That’s placed the stories of people like Cashion in the center of Tennessee’s debate over medical cannabis.

Increasingly, supporters of medical cannabis are pointing to such cases as proof that many conditions can be managed better with marijuana than pharmaceuticals. But opponents say the evidence is anecdotal — at best — and that there isn’t enough controlled research on marijuana to justify medicinal use.

Across Tennessee, there appears to be wide public support for medical cannabis. Forty-four percent of the state’s voters say it should be approved, with an additional 34 percent saying it should also be allowed recreationally. Only about one in five Tennesseans disapprove of cannabis.

But despite years of debate in Tennessee, medical cannabis remains illegal, so using comes at a cost.

Cashion is facing trial. Her case began in October, when police stopped her for running a stop sign just a few feet from her home in downtown Lewisburg. According to a citation, they noticed a green leafy substance and a glass pipe.

Cashion was cited for the traffic violation, simple marijuana possession, possession of drug paraphernalia and driving with a revoked license. She believes that police knew about her cannabis use and hoped she’d give information about her supplier.

But Cashion says the legal risks have been worth it. Since she started using cannabis, she says she’s gradually weened herself off painkillers. She claims it’s been 10 months since she took opioids and three months since she took any prescription drug at all.

“I know that I can function a whole lot better than when I was on the prescription meds,” she says. “And I know that anybody that knows me, will say that. Whether they’re for or against medical cannabis, (they) can’t deny that.”

Limited research

A 2014 paper published in JAMA Internal Medicine suggests that Cashion might not be alone. Researchers found that states that adopted medical cannabis in the late 1990s and 2000s saw fewer overdose deaths than projected.

They calculated a nearly 25 percent drop in opioid mortality, and the gap between states that legalized medical cannabis and those that didn’t increased over time. What’s more, by looking at states before and after legalization, researchers were able to control for factors like geography and different states’ cultural attitudes toward marijuana and opioids.

Republican state Representative Jeremy Faison says that in the years since that research, the epidemic of prescription drug abuse has only worsened.

“I’m realizing that, we’ve been lied to,” he says. “I’ve met thousands of Americans and thousands of Tennesseans who are well, who are doing good, who are benefiting, who are not hooked on a pill.”

State Rep. Jeremy Faison, right, chats on the floor of the state House of Representatives.

Faison has been pushing legislation, House Bill 1749, that would legalize medical cannabis for a host of conditions: diseases such as cancer and hepatitis C; chronic conditions, including nausea, seizures and severe pain; and some mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Faison’s legislation would allow cannabis to be vaporized, but not smoked. He says that’ll make it harder for people to misuse it recreationally, and it’ll allow greater control over supplies.

Growers and distributors would be tightly regulated, and the entire system would be overseen by a new commission.

Faison says the idea is popular in the rural East Tennessee district he represents.

“We have people in Jefferson County and Cocke County and Greene County — all of my counties — have reached out to me and said, ‘Jeremy, either A, I’m illegally using right now or B, I would love to get off all these prescriptions, I would love the opportunity to try something that’s natural, that’s a botanical, that God gave us and put on this planet.”

Opposition has mainly come from doctors. Most agree cannabis can kill pain, but they argue that pills, including those that contain the active ingredients in marijuana, are a safer method.

David Reagan, the Tennessee Department of Health’s chief medical officer, says far too little is known about cannabis’ potency and side effects.

“In order to understand the dose that would be needed and the types of patients that would be likely to benefit, that one would need to have substantially more information for the majority of conditions listed in this bill,” he says.

Federal restrictions

Such complaints frustrate Chinazo Cunningham, a physician at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City. She co-authored the paper that suggested medical cannabis can curb opioid deaths.

Cunningham agrees that more information is needed on cannabis, including studies that can show which doses are needed for particular conditions. But she says the federal governments restrictions on marijuana research has hampered efforts to find those answers.

“It’s really unthinkable that we don’t have the research to help guide the policy,” he says.

Cunningham and her colleagues have been able to study only big-picture questions, such as the effect changes in cannabis law can have statewide.

But New York’s recently enacted medical cannabis law — which is similar to the proposal in Tennessee — has opened the door for researchers. Cunningham and her colleagues have just launched a five-year study of individual pain patients. They want to know whether dependence on painkillers goes down once patients start using cannabis.

“As a physician, this is what we tend to see,” she says. “People who use marijuana report having better pain control and having to use their opioids less.”

Meanwhile in Tennessee, Cashion still faces possible jail time. She’s due back in court this week.

“It’s really sad that I can go and get the strongest opiates and pharmaceuticals that they make, but a plant that’s never killed anybody, they want to put me in jail over.”

Cashion hopes to convince a jury to let her use cannabis, regardless of the law.

credit:420intel.com