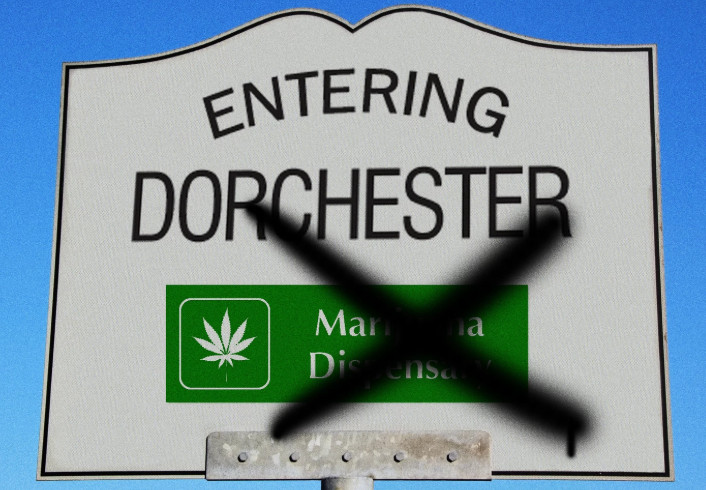

Benjamin Virga was in trouble and he knew it. The Boston businessman had submitted an application to open a high-end weed dispensary in the city’s Dorchester neighborhood, the largest and among the most diverse in town. But now he found himself in a room with frustrated residents of all ages, many of whom were armed with decades of facts and history about their community—a place that has sometimes struggled with drug abuse, violence and poverty.

During the course of the civic meeting last Thursday, fists were slammed on desks, tears welled up, and words were caught in throats. At one point, a woman stood up and shouted, “Never, never, never!” If Virga, an outsider, wanted to bring legal weed to this neighborhood, he needed to convince at least some of miffed locals in front of him first.

It was not going well.

“I understand there’s a newness, and a lack of trust, and a cultural divide,” Virga said in his closing remarks, promising further dialogue. Still, the room brimmed with tension even after he left.

Massachusetts began the process of legalizing pot back in November 2016 with a referendum that passed by a solid but less than robust margin: 53.7 to 46.3 percent. For months now, the state has been collecting applications for marijuana dispensaries, labs, researcher facilities and other related businesses; 73 of them were being reviewed as of July 12. But residents told VICE that prospective dispensary owners—some of whom have eyed economically strapped, working-class neighborhoods with relatively low rent—have shaped their business models in ruthless fashion, chasing profit at the potential cost of local good.

Which is to say despite the obvious benefits of legalization, the new and growing business of weed in America can sometimes feel like just another late-capitalist threat to the place you live.

The opposition in Dorchester—which, like any community in the state, gets to vet a potential pot dispensary before it can open—was not one-note. Some residents were worried about logistics, arguing Virga’s dispensary was proposed on a tiny residential road residents said couldn’t handle more traffic, and had no parking space. It could also oust a local Cape Verdean restaurant, Kriola, since Virgas and his partner were looking to buy the whole building. (The owners of the restaurant, who were at the meeting, said they hadn’t been informed of any changes yet.)

“I voted in support of legalization,” Bob Jones, a Dorchester resident, said at the meeting. “But this is the wrong location.”

Others were concerned about putting more drugs of any kind—even weed—on the street in a neighborhood where alcoholism, the opioid epidemic, and crime have long loomed large. South Dorchester was second only to the South End of Boston in ER visits due to substance-related issues and overdoses in a report that looked at data from 2010 to 2015. And it had higher rates of aggravated assault and robberies than the majority of Boston neighborhoods as of 2015.

“How is this going to help us? We were already boycotting liquor,” resident Sam Jones asked during the meeting. In the past, the community has protested rowdy bars, and in 2016, tried to shut down Kriola’s quest for a liquor license in the same exact location. Virga, for his part, pushed back by citing a Journal of Urban Economics report that found closing dispensaries may have increased crime in adjacent areas in Los Angeles.

Meanwhile, in Chelsea, a 40,000-strong city flanking Boston, some residents worried pot dispensaries would draw the wrong crowd: people determined to get super high and disturb child-friendly neighborhoods, City Councilor Damali Vidot told me outside of City Hall last week. A heavily immigrant and working-class community, Chelsea has also struggled with crime, poverty and a housing crisis in the face of national trends toward gentrification. It has received two applications for dispensaries so far, according to Vidot.

In an interview, Massachusetts Cannabis Control Commissioner Shaleen Title said zoning issues were important when it came to determining the location of a dispensary. But she argued that the businesses themselves “are not any better or worse for working-class communities or minority communities than any other community.”

Title also noted that Massachusetts has actually focused on these communities in hopes that pot shops might boost their economies. When the state crafted its plan for recreational weed, it included provisions giving priority to communities disproportionately impacted by drug criminalization. This includes people with drug-related criminal records, who are otherwise legally able to work. In neighborhoods that have struggled with drug and marijuana arrests, like Dorchester, Title said it’s even more critical that residents are involved in the business.

In Chelsea, Vidot—who said she supports the state marijuana program—said she was hopeful the dispensaries would bring jobs and tax revenue to the community. “We’re getting paid at the end of the day,” she noted, adding that applications the city had approved were for dispensaries in the industrial areas of the city, which made her think safety concerns weren’t quite as pressing.

Even in 2018, it’s tough to predict what impact dispensaries might have on a given community. Colorado, for instance, has enjoyed a windfall of hundreds of millions in new tax revenue since legalizing weed, some of which has been spent on local priorities like education. But the state has also seen increased hospital visits stemming from marijuana-related burns and edible consumption. While there have been fewer marijuana-related arrests in legal-weed states, arrests still disproportionately burden black people and communities of color.

And while the Massachusetts policy was designed at least in part to directly address disparities in who profits, white people have so far tended to benefit the most from pot legalization nationally, according to a 2015 analysis in the University of California Davis Law Review.

At the Dorchester meeting, Virga said his business was a way of boosting the local economy without changing the demographics of the neighborhood, which is largely comprised of people of color. “This is a neighborhood tool that doesn’t involve gentrification,” he insisted, telling me after the meeting that his dispensary would push out the small percentage of the population that was causing a spike in crime rates in the neighborhood, too. “I think that 95 percent of the population that were impassionately speaking in there, and handing me my hat… I think it’s going to help them experience a higher quality of life.”

The rent piece of this is difficult to parse, since various forces determine the housing market of any given neighborhood in a large American city. Title noted people looking to set up cannabis retail shops look for properties to rent or own just like any other type of business. But in Denver, pot businesses boosted property values in their host neighborhoods, according to a report last year from the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Business. In other words, the business of weed can be both a boon to homeowners and a source of stress on local renters.

With these questions up in the air, residents in some of Massachusetts’ most vulnerable neighborhoods were determined to prevent pot legalization from further destabilizing their communities—even if the broader trend toward acceptance of weed seemed irreversible.

“Why aren’t you putting this where you live,” resident Robert Mickiewicz demanded of Virga during the meeting in Dorchester. “You want to put it here in Dorchester, where you dump all that stuff.”

Credit: www.vice.com/