On Oct. 15, something strange happened.

A law enforcement officer delivered a box of marijuana to a Danville house. But that officer was not going outside of the law.

It was a drug bust.

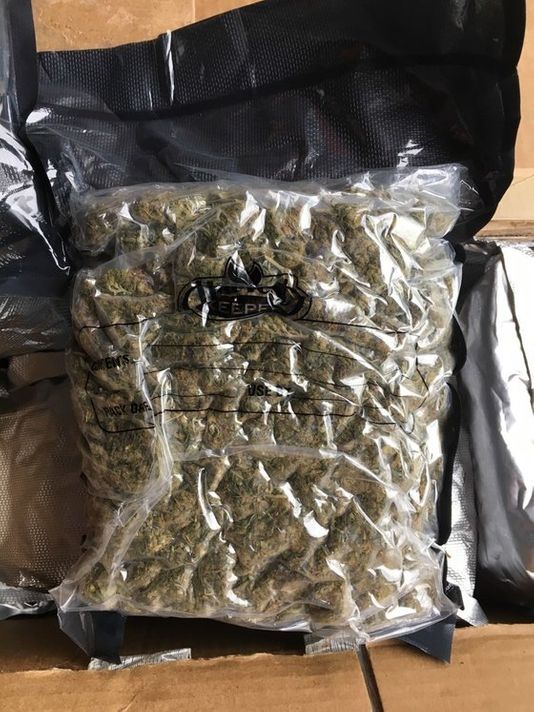

City police were conducting what they call a “controlled delivery” of the 18-pound box, which they found to be full of weed, to Robindell Court, according to a search warrant recently filed in Danville Circuit Court.

A controlled delivery, Danville Police Department Lt. Mike Wallace explained, is when law enforcement drops a questionable package off at its destination after moving through the U.S. Postal Service or a private carrier. Post office inspectors or a tip can point police to a suspicious package — some of which contain drugs. If necessary, officers can dress as letter carriers from multiple services to better sell the drug bust.

“Most of the major transport companies as well as the U.S. mail” are used to deliver drugs, Wallace said. “We have had cooperation with all those companies.”

U.S. Postal Service investigators initially became suspicious of this particular box — bound for a house in the western edge of Danville — four days before the package landed at the doorstep, the search warrant states.

The postal investigator who first questioned this particular delivery noted it was from Santa Rosa, California — “a known source area for controlled substances,” states his search warrant in U.S. District Court in Roanoke — and the sender’s address and name did not match any information available in an electronic database. The recipient’s name and address did not add up either, so the parcel was sidelined. A Virginia State Police drug dog gave it a sniff-test, which it failed.

Investigators had to get a search warrant for the box because it was sent as priority mail express, used for larger packages, which is difficult to search without a warrant, retired postal inspector John Rooney said. A search warrant is not needed for some other types of mail, however, according to the postal service’s website.

Rooney was a postal inspector in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for 30 years before retiring in 2001. He said that tried-and-true techniques of establishing patterns — where a package comes from and where it goes — have proven effective in halting the flow of drugs through the postal service. That flow, he said, is “impossible” to completely halt, often originating in California.

“Primarily they come out of California,” he said. “And you look for patterns”

Rooney said tons of marijuana was coming into the U.S. during his time as an inspector, and it still does.

“It’s coming in seven days a week,” he said. “Dope came in 24/7.”

Often, drug dealers looking to ship their product use fake names and invalid addresses, the federal warrant states. That, Wallace said, makes the job of local police more frustrating when it comes to making an arrest.

“If you’re going to arrest a person, you have to know who that person is,” he said. “You need some definite information to get to the person.”

Postal investigators have seized approximately $71 million in drug money and assorted drugs since 2015, according to annual reports. Approximately $22.5 of that came in 2017 alone — along with nearly 2,000 arrests tied to mailing narcotics.

Beyond a package’s place of origin or listed addresses, the parcel’s weight factors can also arouse suspicion when paired with its original and receiving addresses, Rooney said. Express mail’s advent also has made it quicker for drug dealers to send product and receive payment.

“Inside of three days you’ve sent your drugs… and the next day or the day after, the money can be sent back to the drug dealer or the source,” Rooney said.

Postal investigators — who wield the same power of arrest as any other federal law enforcement agents — can investigate drug cases themselves, Rooney said. But if they bring a case to the U.S. Attorney for a district and they are not interested in its prosecution, postal investigators can tip off local police to the suspicious package.

Before local police attempt a controlled delivery, they need solid information, Wallace said. Just because California is known for drug distribution does not mean all packages from California to Danville are investigated.

“Consider the number of packages that come out of California. That number has to be narrowed down,” Wallace said. “Just coming from California is a criterion that is way too broad.”

The Danville warrant states it would only be executed if the package was accepted into or seen leaving the residence, the package’s security was at risk, or if “the safety of the officer conducting the controlled delivery is at risk.” If none of those criteria were met, the warrant would be rendered moot and returned to the issuing magistrate, the document states.

But police listed a white cellphone and a box containing marijuana as items seized during a search of the house, indicating the warrant was executed. Wallace did not know if the delivery resulted in an arrest and a search of recently filed charges did not show any related to that particular address.

The U.S. Postal Inspection Service did not respond to multiple requests for interviews for this story.

Credit: www.godanriver.com