Sally Hampton and her father, Bill, were both diagnosed with debilitating health issues one year apart. The bad news struck Sally first: In August 2016, the former Hollywood film and TV writer and producer was suffering recurring headaches so bad she felt like her skull might explode. Doctors did an MRI and discovered what appears to be a meningioma, a slow-growing brain tumor pressing against her brain. It was in a tricky spot, so she balked at the idea of a high-risk surgery, which, general disfigurement aside, she says could have led to neurological complications or even death.

Then in late August 2017, Sally’s dad, a former Marine and retired high school principal living in San Diego, learned he had bladder cancer. Doctors scraped out what they could find and recommended chemotherapy. Bill balked at that, too. He was already in his eighties, and didn’t want what might be his last years to be spent suffering side effects from the treatment.

So far, Bill’s cancer hasn’t made a recurrence, and he seems more lucid and upbeat. Sally’s headaches have reduced, she can sleep again, and, while she recognizes marijuana isn’t a miracle drug, her last check-up about two months ago marked the first time there was no evidence of additional tumor growth. (Jetty doesn’t make formal recommendations for how to use weed as medicine, or claims about its effectiveness.)

The Hampton’s lives feel improved; they’re believers in the benefit of medical marijuana, so much so that Sally thinks it may even be helping with some of Bill’s other health issues, of which there are many. “It completely changed our opinion of cannabis,” she says. “And those people [at Jetty], as far as I’m concerned, are angels.” The problem now is that she has no idea when her next delivery might arrive–if ever. Earlier this year Jetty sent word that its compassionate care efforts would have to be suspended. The lapse affects more than 500 clients. The Shelter Project’s website carries the announcement: “Due to California state cannabis laws and regulations, we are unable to enroll patients in the Shelter Project at this time.”

In passing laws to make marijuana fully legal, state lawmakers inadvertently derailed the pipeline that has been operating for years to donate marijuana to sick people in need. Existing compassionate care programs led by both commercial and nonprofit organizations can’t operate in the new climate because there is no way to officially license their services, and, even if so, they’d still be subject to taxes so high many operations would have to fold.

In late May, state legislators acknowledged the problem by introducing a new bill that might ultimately rectify both issues, allowing groups to operate with their own legal designation in order to avoid the tax penalties. There’s a provision for farmers, too, many of whom give to compassionate care groups but currently face a steep cultivation tax on those donations. In the meantime, the irony remains thick: Compassion groups have operated for years under intense scrutiny from drug enforcement officials, only to see the most sweepingly progressive shift in state history snuff them out.

“UNDER CURRENT LAW, CANNABIS CANNOT BE GIVEN AWAY”

In January 2018, Proposition 64 took effect in California, making recreational marijuana sales legal within the state. California’s new Bureau of Cannabis Control assumed the duty of helping growers, manufacturers, distributors, and dispensaries conform to a new permit and licensing process that makes the entire supply chain more transparent, so that product flows can be traced, tracked, and heavily taxed.

While the law makes it legal for anyone 21 and over to buy weed from sanctioned shops, that hasn’t produced quite the boom that California imagined. Just a couple months into the new era, sales were already 13% behind initial market projections of about $1.2 billion this year, in part because many dispensaries are struggling operate in the supposedly more permissive environment, which requires gaining both state and local business approvals. (Some municipalities are still working out that permissions process.)

According to the Sacramento Bee, there were as many as 6,000 dispensaries operating inside the state in February. But fewer than 600 had received formal state certification to sell recreationally. Many of those other spots were likely granted temporary licensing extensions as they struggled with the fine print. But for customers finding a reliable outpost might be challenging. The state’s own locator has been disabled on its website and some places have shut down completely or may be about to: Regulators recently sent cease and desist orders to over 900 sellers on the marijuana dispensary locating service Weed Maps.

What’s now legally available is now both scarcer and more heavily taxed than before: Prices peaked at $45 an ounce in January. And because customers who don’t like the high prices can still buy from the black market, Ron Gershoni, the CEO and cofounder of Jetty estimates that revenue has dropped from 50% to 70% among many brands. “It’s pretty much hurt every business [that] has gone for licensing and that would include Jetty,” he says.

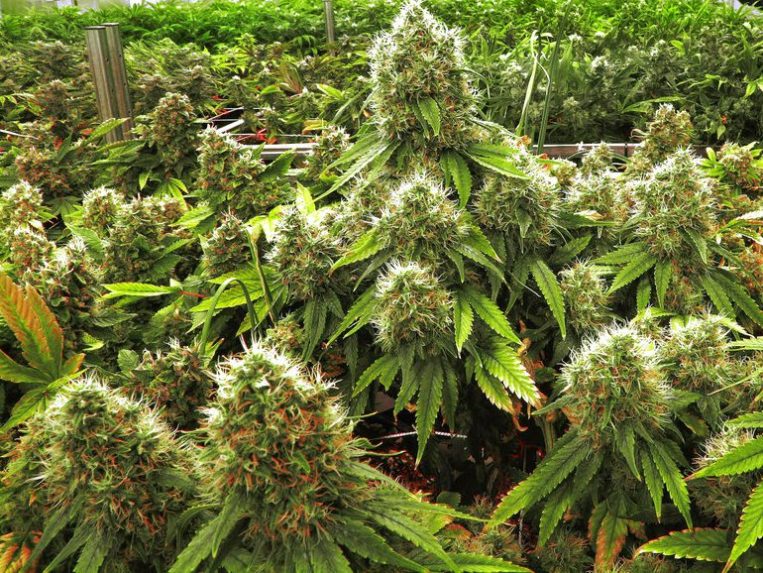

In California, there have traditionally been two kinds of marijuana-related compassionate care programs. The most common is a traditional stand-alone operation, which operates without profit to collect bud from growers or suppliers and redistribute it to patients. (A few are vertically integrated, growing everything they donate). Then there are manufacturer- or dispensary-run efforts like the Shelter Project; these do much the same thing, but allocate directly from their own inventories as a sort of in-house philanthropy unit.

For in-house programs, Prop 64 made the entire donation process illegal by technicality. The only distribution point for any product must be a licensed dispensary, and nothing can leave stores for free. “Under current law, cannabis cannot be given away. Everything must be tied to a sale,” says Bureau of Cannabis Control spokesman Alex Traverso in an email to Fast Company.

Jetty is a manufacturer and distributor. So even if it were to fund patients to buy their own goods, the company would owe taxes based on the retail value of their product. This includes a 15% excise tax, local use charge, and, for some groups, general cultivation fees, which can be nearly as large. Sally Hampton estimates she and her dad together may each be receiving at least several hundred of dollars a piece in donated marijuana per month. Over the course of a year, that alone would cost Jetty at least $1,000 in excise fees–for just two people.

“The original battle cry to fix compassion was because people had either stopped donating cannabis or they were having to pay upward of 38% or more in taxes alone,” says Anne Kelson, a law and policy advisor for the California Compassion Coalition, which represents about 20 traditional groups serving 3,000 people throughout the state. “It’s not necessarily something that was intentional, but people believe that there was a lot of focus [by California lawmakers] on getting the adult-use market online . . . and a lot of compassion donations were kind of overlooked.”

THE HISTORY OF COMPASSIONATE CARE

California’s quest for legalization has deep roots in compassionate use. In 1996, voters passed Proposition 215, also known as the Compassionate Use Act, which allowed doctors to recommend medical marijuana to patients for all types of maladies–everything from AIDS to cancer, chronic pain, and glaucoma. (The proposal mimicked city-based legislations that had been adopted a few years earlier in San Francisco.)

Traditionally, marijuana has been prescribed for nausea relief, to improve appetite, and as a sleep aid, but, because criminalization slowed formal medical studies, many of its benefits are anecdotal. By empowering doctors to use their own discretion, the drug has become a popular salve for other things like headaches and anxiety, although critics feared people would fake symptoms to game the system.

Proposition 215 decriminalized the possession of small quantities of the drug for medically prescribed patients and their caregivers, too, which gave rise to the co-op model. For years, dispensaries and aid groups both collected physician recommendations to justify contracts with growers and the quantity they were handling. Those patients could also apply for medical marijuana cards to signal their status to law enforcement. But weed still wasn’t free, which has always posed a problem for those with severe or chronic illnesses that otherwise couldn’t afford it.

Joe Airone is the founder and director of Sweetleaf Collective, a compassionate care organization that has been operating since 1996 and serves 150 terminally ill patients in the Bay Area. He’s also a member of the California Compassion Coalition, which is comprised of organizations that have other specialties, like the Weed for Warriors Project to support veterans or Caladrius Network for extremely sick children.

In the mid-90s, Airone was inspired to create a pot-focused philanthropy after working with Food Not Bombs, another San Francisco group that convinced grocers to donate food that might otherwise be thrown out to volunteers who cooked meals for the homeless. Today, Sweetleaf does pretty much the same thing for flower growers that end up with buds that are too little, old, or blemished in a way that makes them less marketable. “It’s kind of the equivalent in the food industry of carrots that look weird,” he says.

Sweetleaf eventually formalized into a not-for-profit mutual benefit corporation, a state designation that all compassionate weed groups used to justify their co-op structure. Because they handle a federally controlled substance, they’re not allowed to organize around the typical 501c3 designation. The co-op format gave groups a legal defense, but each still has to work out a process that makes it clear they’re not enabling drug abuse. Many compassion groups served patients who were already being seen by doctors and social workers, who could justify their medical diagnosis and financial hardship.

All of this is bootstrapped: Because they’re not federally recognized nonprofits, these groups can’t offer tax-incentives to donors, making it far less likely that they’ll receive philanthropic gifts. Sweetleaf, for instance, delivers by bicycle to save cost, giving away about 100 pounds of bud per year. Even if they could operate under the new system, Airone says there’s no way they could afford the taxes, which might range between $50,000 and $200,000 per year.

Before January, Airone gave all of his patients extra-large deliveries to last them longer than usual and then notified them that he’d have to discontinue service while he challenged the new law. It’s a short-term risk that he feels forced to take. After 20 years in operation, he didn’t want to openly flout the law and watch everything he’d worked for potentially combust.

At the same time, the need couldn’t be more urgent: “For example, with HIV and wasting syndrome you can have a patient lose 50 pounds in a month. And we haven’t been able to get them medicine for months now,” he says. Nearly 2,500 people have since signed a Change.org petition that Sweetleaf started to create separate regulations for compassionate care programs, but that doesn’t speak for the droves of folks that would sign but can’t anymore. Unfortunately, Sweetleaf’s waiting list moves fairly quickly, as an extremely ill patients regularly pass on.

“THERE’S A MASSIVE AMOUNT OF CONFUSION”

In mid-March, after hearing testimony from patients who had lost their donated pot, a California state subcommittee on public health recommended legislators create emergency “state and local licensing processes” for compassionate groups. A month later, the state’s department of tax and fee administration declared that the excise tax should not apply to free medical cannabis given to qualified patients–and any group that may have paid exorbitant fees to stay operational is likely eligible for receive refunds.

In the meantime, the BCC and other state officials have been working through a joint advisory committee to figure out how compassion programs should be greenlit and allowed to work. Kelson, the Compassion Coalition advisor says her group is still working on knocking off local and cultivation taxes and has seen some support from officials on that front. “Unfortunately it’s the government, so as ‘soon as possible’ is a lot slower than we would like to see happen,” adds Airone.

Kelson tells Fast Company that some groups might still be operating, albeit clandestinely or through loopholes they think may be defensible but aren’t not openly advertising. “[They] wouldn’t necessarily tell you that because they may want to be able to save lives, but they also don’t want to have the penalties associated with it,” she says.

Commercial operators face a different kind of math. “There’s a massive amount of confusion,” Jetty’s Gershoni says. “It’s been difficult to really get a very clear answer on exactly how we can do it. Getting compliant is kind of a tornado of work and jumping through hoops. This is one component of that, and we’re kind of in the process constantly of doing both.”

“We are lobbying to waive all taxes on compassion programs and believe that anyone who’s giving away free product to people who really need it for medical purposes should be able to do that without having a cost and tax associated,” he adds, echoing the stance of the coalition. It’s pretty fundamental business logic that if sales are down and you face an uncertain market, you may not want to experiment with ways to dole out free product that could actually cost you more money. But it’s not like Jetty is on the verge of bankruptcy. In April the company agreed to be acquired by the Canadian investment firm Cannex Capital for an estimated $30 million, with the deal set to close in July.

Even if all costs do get waived, there’s the logistical hurdle of having to run everything through a dispensary, upping training and staffing costs for someone along that supply line, especially because many patients need their medicine delivered. No matter how the legal smoke settles, Gershoni says that it is likely that Shelter Project costs will still increase.

It’s a delicate trade-off, because this sort of compassion work is governed by an obvious commercial reality. Company-based charity efforts hinge on profitability. Even if companies consider this a marketing line item, the impact hinges on being able to reach many people as possible cheaply.

WHAT COMES NEXT?

The legal haze certainly slowed new efforts at one of the industry’s biggest players. Jennifer Lujan is the director of social impact at Eaze, an online retailer that operates a lot like Amazon but for cannabis. (She worked previously in a similar role at Lyft.) The company started in mid-2014 and claims to currently serve about 350,000 customers in California, delivering in most major California cities, and working with about 60 brands. In April, Eaze pledged to spend $1 million over the next three years to improve social equity in the Bay Area. For perspective, it has $52 million in funding and counts Snoop Dogg as an investor.

As the marijuana market opens, Lujan says Eaze hopes to create a broad range of initiatives that nurture community businesses and empower people whose lives were once disrupted by drug laws and incarceration. Ideally, that would include supporting compassion programs in some way, too.

But while Lujan says many industry suppliers have expressed interest in donating, especially given how it aligns with their original missions, the ambiguity has made taking action difficult. “I still get all the time people who think that, yes, we could still be donating,” she says. “But right now a lot of compassionate care programs just had to pause for a bit to kind of figure it out. That includes a compassionate group that Lujan founded in 2015 called Weed For Good, which provided services for another 100 terminally ill and low-income people in the Bay Area. Since it’s inception, the group has donated $175,000 worth of product, she says, but isn’t currently operating.

State regulators still didn’t have a way to fully estimate the scope of the problem. “[W]e don’t have or keep any list associated with these nonprofits,” the BCC’s Traverso added in his email. However, he suggested at least one workaround to keep donated products moving: Dispensaries could theoretically “charge a dramatically reduced amount, but the taxes associated with that product must still be paid.”

It’s unclear whether commercial operators will try that fix without formal approval. Like so many other places, Gershoni says Jetty stocked recipients up with extra-large shipment just ahead of the law change. But Sally Hampton says that she and her father will both be out of their current supply shortly, leaving them few options but to try to source something similar from wherever they can find it, and as cheaply as possible. For the first time since recent memory, she’s incredibly anxious.

Credit: www.fastcompany.com